Implementing parsers

Introduction

Once we have tokenized some program text, we need to check whether the tokens are in the correct sequence. For example, which of the following token sequences are valid?

- Tokenization of “32 + 4”: “<number, 32>, <+, +>, <number, 4>”.

- Tokenization of “+ 32 4”: “<+, +>, <number, 32>, <number, 4>”.

Regular expressions are not powerful enough to make the choices like these. The rules about which token sequences are valid constitute the syntax of a programming language. In this article, we will develop the concepts and techniques of checking syntactic correctness of a program text.

We will assume that the program text is already tokenized. Thus, our input is going to be a sequence of tokens. The tokens we will be dealing with in this article are as follows.

- The token “number” represents positive integers.

- The token “id” represents identifiers.

- The symbols “+”, “-“, “*”, “/”, “=”, “==”, “)”, and “(“ represent themselves.

Here are some examples of raw inputs along with their tokenized represenations.

| Raw input | Tokenized representation |

|---|---|

| "123 + 13132" | number + number |

| "123 * 234 + 12" | "number * number + number" |

| "(978 * 13) / (123 - 12)" | "(number * number) / (number - number)" |

For brevity, we will call a sequence of tokens a string.

Context-free grammars

We need a way to represent programming language syntax. Let’s start with a simple example. Suppose we want to represent those arithmetic expressions where two positive integers are separated by a “+” sign. We can represent this idea using the following notation.

\[expr \rightarrow \underline{number} \underline{+} \underline{number}\]This is an example of a production. There are two parts separated by an arrow. The symbol “expr” on the left of the arrow is the head of this production. The symbols “number”, “+”, and “number” on the right are collectively the body of this production. The underlined symbols appear in the input and are called the terminals. Symbols that are not terminals are called the non terminals.

Only “number + number” conforms to the above production. To represent “number + number + number”, we need to write a new production.

\[expr \rightarrow \underline{number} + \underline{number} + \underline{number}\]What if we want to represent an unbounded number of “number” tokens separated by “+” signs? The phrase “an unbounded number” suggests induction. We need atleast two productions to represent an inductive definition.

\[\begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number} \\ expr & \rightarrow \underline{number} \end{align*}\]In the above set of productions, the second production is the basis case and the first production is the inductive case. Before we can use this set of productions to represent something like “number + number + number”, we need to define a new concept.

In a set of productions, if we designate a non terminal as a start symbol, we have a context-free grammar.

Definition 1: Context-Free Grammar

A context free grammar is a 4-tuple \(\{V, \Sigma, P, S\}\) where:

- \(V\) is a set of non terminals.

- \(\Sigma\) is a set of terminals.

- \(P\) is a set of productions.

- \(S\) is a non terminal designated as a start symbol.

We can thus use our above pair of productions to create a context-free grammar.

Addition grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number} \\ expr & \rightarrow \underline{number} \end{align*} $$In the above grammar:

- \(V = \{expr\}\),

- \(\Sigma = \{number, +\}\),

- \(P\) is the set of productions, and

- \(S = expr\).

A string is a member of a grammar if it can be derived using that grammar. Let us derive “number + number + number” using our addition grammar. We start with the start symbol.

\[\begin{align*} expr \end{align*}\]We apply a production by replacing a non terminal with its body. So the application of \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number}\) is this.

On that \(expr\) in the string, we apply the same production \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number}\).

Finally, we apply \(expr \rightarrow \underline{number}\) on the \(expr\) in the last string. The result is the string we wanted to derive.

Definition 2: Derivation

The sequence of steps taken by a grammar to produce a string starting from the start symbol of the grammar is called a derivation.

The above derivation of “number + number + number” is this.

\[\begin{align*} & expr \\ \implies & expr + number \\ \implies & expr + number + number \\ \implies & number + number + number \end{align*}\]Context-free grammars describe languages. The langauges defined by context-free grammars are called context-free languages.

One unknown in the above derivation is the choice of production to apply at each step. How did we know that we should apply \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number}\) on all but the last step and \(expr \rightarrow \underline{number}\) on the last step? This problem is central to syntax checking and we will address it over the course of the remaining article.

With context-free grammars, we have a notation to represent the syntactic elements of a programming language.

Reductions

In syntax checking, we are given a grammar and a string and we want to check whether the string is in the language of that grammar. We need to find the derivation of that string using the grammar.

A more convinient way to look into this problem is to look at derivations in reverse. The above derivation of “number + number + number” in reverse looks like this.

\[\begin{align*} & number + number + number \\ \implies & expr + number + number \\ \implies & expr + number \\ \implies & expr \end{align*}\]We are finding instances of production bodies in the string and replacing them with production heads. This process of replacing an instance of a production body with a production head is called reduction. Reduction is the opposite of the application of a production. We can now state the condition under which a string belongs to a context-free language.

Definition 4: Criterion for a string to be derivable from a grammar

A string can be derived from a grammar if we can reduce it to the start symbol of that grammar.

Extending context-free grammars

The addition grammar is contrived. Because of that, we have not uncovered the full complexity of derivations and reductions. Before moving further, we should learn about extending context-free grammars.

Context-free grammars are defined inductively. Thus, we can extend a context-free grammar by adding more inductive cases as productions. Let’s try to extend our arithemtic grammar. Right now, it can only handle the “+” operator.

Addition grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number} \\ expr & \rightarrow \underline{number} \end{align*} $$We now want to add support for the “*” operator. We can do that by adding more productions to our addition grammar.

Addition and multiplication grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term \\ expr & \rightarrow term \\ term & \rightarrow term \underline{*} \underline{number} \\ term & \rightarrow \underline{number} \end{align*} $$We replaced the terminal \(number\) in our addition grammar by a new non terminal \(term\) and added basis and inductive productions for \(term\).

One way to add more induction cases is to introduce new non terminals. This is what led us from addition grammar to addition and multiplication grammar. Let us look at another example. If we want to handle parenthesized expressions like “(123 + 12) * 3”, we can extend our addition and multiplication grammar like this.

Addition and multiplication with parenthesis

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term \\ expr & \rightarrow term \\ term & \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow f\!actor \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{number} \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{(} expr \underline{)} \end{align*} $$We replaced \(\underline{number}\) in addition and multiplication grammar by a new non terminal \(f\!actor\) and added two new productions for \(f\!actor\). The production \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\) is the basis case and \(f\!actor \rightarrow (expr)\) is the inductive case.

We can add inductive cases to our grammar without introducing new non terminals by changing the way non terminals are arranged in production bodies. Let us extend our grammar to handle “" and “-“ operators.

Complete arithmetic grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term \\ expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{-} term \\ expr & \rightarrow term \\ term & \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow term \space \underline{/} \space f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow f\!actor \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{number} \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{(} expr \underline{)} \end{align*} $$That is, we added two new productions, \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{-} term\) and \(term \rightarrow term \space \underline{/} \space f\!actor\) without changing anything else.

The complete arithmetic grammar is realistic enough for us to elucidate points we would otherwise have missed had we continued with our original addition grammar.

Implementing reductions

Let us go back to the problem of implementing reductions. The implementations of reductions, and of grammars, are called parsers. The process of reducing a string of tokens to the start symbol of a grammar is called parsing.

Let us reduce “(number - number) * (number / number)” using the complete arithmetic grammar. To get started, here is the derivation of “(number - number) * (number / number)” using the complete arithmetic grammar. Notice that at each step, we apply a production to the rightmost terminal. This technique is called the rightmost derivation.

Doing the derivation in reverse results in the reduction of the input to the start symbol.

Because we already know how this particular input is reduced, we can use the above steps as our guide and focus on the data structures and the algorithms we can use to represent this process. We will then use those techniques to parse new inputs.

Suppose the input is an array of tokens and we have an empty stack. In the following illustrations, the top of the stack is on the right. The initial state looks like this.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((number - number) * (number \space / \space number)\) |

We will apply one of the following two operations at each step.

- We shift a token onto the stack. This is called performing a shift.

- We identify the stack contents with a production body and perform a reduction on part or all of the stack. This is called performing a reduce.

The parser variant we are considering is called a shift-reduce parser.

Once we shift the first token, we have the following parser state.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((\) | \(number - number) * (number \space / \space number)\) |

Let us shift one more token on to the stack.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((number\) | \(- \space number) * (number \space / \space number)\) |

Before doing any more shifts, we need to reduce the top token of the stack \(number\) using \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\). This is suggested by the reduction steps we described above.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((f\!actor\) | \(- \space number) * (number \space / \space number)\) |

Looking at the above reduction steps, we need to reduce again, this time with \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((term\) | \(- \space number) * (number \space / \space number)\) |

Using the above reduction steps again as our guide, we do another reduce using \(expr \rightarrow term\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr\) | \(- \space number) * (number \space / \space number)\) |

We now do two shifts.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr\space-\) | \(number)* (number \space / \space number)\) |

| \((expr - number\) | \()* (number \space / \space number)\) |

We next do two reductions on the top symbol, one using \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\) and another using \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr - f\!actor\) | \()* (number \space / \space number)\) |

| \((expr - term\) | \()* (number \space / \space number)\) |

So far, we have been reducing only the top symbol. Our next reduction is going to use the top three tokens using the production \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{-} term\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr\) | \()* (number \space / \space number)\) |

We shift again.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr)\) | \(* \space (number \space / \space number)\) |

We now reduce the entire stack contents using the production \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{(}expr\underline{)}\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(f\!actor\) | \(* \space (number \space / \space number)\) |

In the steps we have executed so far, we notice two things.

- We need to decide whether to shift or to reduce at each step.

- We need to select a production whenever we perform a reduce.

We continue executing actions similar to above till we have only the start symbol on the stack. We add a new column of explanations for each of these steps. On each row, the explanation is the action we do to get the next row.

| Stack | Input | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| \(f\!actor\) | \(* \space (number \space / \space number)\) | reduce using \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\) |

| \(term\) | \(* \space (number \space / \space number)\) | shift \(*\) |

| \(term \space *\) | \((number \space / \space number)\) | shift \((\) |

| \(term \space * (\) | \(number \space / \space number)\) | shift \(number\) |

| \(term \space * (number\) | \(/ \space number)\) | reduce using \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\) |

| \(term \space * (f\!actor\) | \(/ \space number)\) | reduce using \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\) |

| \(term \space * (term\) | \(/ \space number)\) | shift \(/\) |

| \(term \space * (term \space /\) | \(number)\) | shift \(number\) |

| \(term \space * (term \space / \space number\) | \()\) | reduce using \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\) |

| \(term \space * (term \space / \space f\!actor\) | \()\) | reduce using \(term \rightarrow term \space \underline{/} \space f\!actor\) |

| \(term \space * (term\) | \()\) | reduce using \(expr \rightarrow term\) |

| \(term \space * (expr\) | \()\) | shift \()\) |

| \(term \space * (expr)\) | reduce using \(f\!actor \rightarrow (expr)\) | |

| \(term \space * f\!actor\) | reduce using \(term \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor\) | |

| \(term\) | reduce using \(expr \rightarrow term\) | |

| \(expr\) |

We now have the mechanism to implement parsing. We either do a shift or a reduce using a stack and an array of tokens. But the above implementation makes decisions at each step and we don’t yet know how to make those decisions. The decisions are:

- Should we shift or should we reduce?

- If we are reducing, which production should we use?

In other words, we have the mechanisms in place but not the policies to drive those mechanisms. We will focus next on changing our above implementation so that it can make those decisions.

Implementing parsing decisions

What are the decision inputs at each step? We have two pieces of information.

- The entire stack that is read from right to left.

- The next token in the array of tokens that we are parsing. In other words, we have a lookahead of one symbol.

To see how these information pieces can be used to make a decision, let’s look at the reduction of “number + number * number”.

We notice that terminals follow non terminals at some derivation steps. For example, terminal \(+\) follows non terminals \(term\), \(f\!actor\), and \(expr\). At one point, the parser state would look like this.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((f\!actor\) | \(+ number * number\) |

We say that we can reduce \(f\!actor\) to \(term\) only if \(+\) can follow \(term\) in a derivation step. That's indeed the case and the parser proceeds.

Therefore, to make progress with the parser implementation, we need to find the terminals that can follow each non terminal of a grammar during a derivation.

Definition 5: Follow set of a non terminal

The follow set of a non terminal is the set of terminals that can follow it in a derivation step.

What happens if a non terminal is followed by another non terminal in a parser state? That’s not possible in our arithmetic grammar above because all non terminals are followed by terminals so let’s create a new grammar to answer this question.

Suppose we want to express C-like declaration statements like “int foo, bar;” or “float temperature;”. Here’s a grammar to represent declaration statements.

Declaration statement grammar

Start symbol: declaration

$$ \begin{align*} declaration & \rightarrow type \space variables\_list \space \underline{;} \\ type & \rightarrow \underline{int} \\ type & \rightarrow \underline{f\!loat} \\ variables\_list & \rightarrow variables\_list \space \underline{,} \underline{variable} \\ variablies\_list & \rightarrow \underline{variable} \end{align*} $$In the first production, we have a non terminal \(type\) followed by another non terminal \(variables\_list\). How can we compute the follow set of \(type\)? Solving this problem requires clarifying what do non terminals represent. We will first clarify what non terminals are before going back to the follow sets.

Every non terminal of a grammar derives strings. In our declaration statements grammar, non terminal \(variables\_list\) derives strings like these.

- "variable"

- "variable, variable"

- "variable, variable, variable"

We can now define the concept of the first set of a grammar symbol.

Definition 6: First set of a grammar symbol

The first set of a non terminal is the set of all possible terminals that can start the strings derivable from that non terminal.

The first set of a terminal is that terminal itself.

Let us look at a couple of examples to make this clear.

In our arithmetic grammar, some of the strings derivable from the non terminal \(term\) look like these.

- "number"

- "number * number"

- "(number) * number"

These strings start with either \(number\) or \((\). Thus, the first set of \(term\) is \(\{number, \space (\space\}\).

In our declaration grammar, some of the strings derivable from the non terminal \(variables\_list\) look like these.

- "variable"

- "variable, variable"

- "variable, variable, variable"

Thus, the first set of \(variables\_list\) is \(\{variable\}\).

We can now design an algorithm to compute the first sets. The definition suggests a recursive algorithm. The basis case is when the grammar symbol we are computing the first set of is a terminal. The recursive case is when the grammar symbol is a non terminal.

To come up with an algorithm, let us look at some examples of how strings are derived from a non terminal. We will use our declaration grammar and compute the first set of the non terminal \(declaration\). Some of the strings derived from \(declaration\), along with their rightmost derivations, look like these.

-

String: "float variable;"

Derivation: \(declaration \Rightarrow type \space variables\_list; \Rightarrow type \space variable; \Rightarrow f\!loat \space variable; \) -

String: "int variable, variable;"

Derivation: \(declaration \Rightarrow type \space variables\_list; \Rightarrow type \space variables\_list, \space variable; \Rightarrow type \space variable, \space variable; \Rightarrow int \space variable, \space variable; \)

Here is how we can compute the first set of \(declaration\).

- Because the non terminal \(type\) derives two single length strings, \(int\) and \(f\!loat\), and nothing else, the first set of \(type\) is \(\{int, f\!loat\}\).

- Because of the production \(declaration \rightarrow type \space variables\_list\underline{;}\), every string derivable from \(declaration\) must start with something that is derived from \(type\). Thus, the first set of \(type\) is a subset of the first set of \(declaration\). Since there are no other productions with \(declaration\) as the head, the first set of \(declaration\) equals the first set of \(type\).

We are now in a position to write down a recursive algorithm to compute first set.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

compute_first_set(grammar_symbol):

if (grammar_symbol is a terminal):

# Basis case

return {grammar_symbol}

else:

# Recursive case

first_set = {}

productions_of_grammar_symbol = get_all_productions_of_grammar_symbol(grammar_symbol)

for production in productions_of_grammar_symbol:

first_symbol_of_production_body = get_first_symbol_of_production_body(production)

if first_symbol_of_production_body != grammar_symbol:

# Recurse

first_set_of_body_symbol = compute_first_set(first_symbol_of_production_body)

first_set.union_with(first_set_of_body_symbol)

return first_set

}

Let us try to find the first set of \(declaration\) in the declaration grammar using this algorithm. We repeat the grammar below.

Declaration statement grammar

Start symbol: declaration

$$ \begin{align*} declaration & \rightarrow type \space variables\_list \space \underline{;} \\ type & \rightarrow \underline{int} \\ type & \rightarrow \underline{f\!loat} \\ variables\_list & \rightarrow variables\_list \space \underline{,} \underline{variable} \\ variablies\_list & \rightarrow \underline{variable} \end{align*} $$The execution looks like this.

Let us do another example, this time with our arithmetic grammar.

Complete arithmetic grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term \\ expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{-} term \\ expr & \rightarrow term \\ term & \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow term \space \underline{/} \space f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow f\!actor \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{number} \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{(} expr \underline{)} \end{align*} $$The execution looks like this.

We can now go back to designing an algorithm for computing follow sets. There are two scenarios under which a terminal can be in the follow set of a non terminal.

The first scenario is when a non terminal is followed by another grammar symbol in a production body. In that case, the first set of the following grammar symbol is included in the follow set of the non terminal. For example, in our above declaration grammar, the first set of \(variables\_list\) is included in the follow set of \(type\).

The second scenario is when a non terminal is the last symbol of a production body. In that case, the follow set of the head of the production is included in the follow set of that non terminal. For example, in our above arithmetic grammar, the follow set of \(term\) is included in the follow set of \(f\!actor\). To see how that could be true, consider an example derivation step using the arithmetic grammar \( expr + number \implies expr + term + number\). Because of the production \(expr \rightarrow expr + term\), every terminal that follows \(expr\) can also follow \(term\). Hence, the follow set of \(term\) must include the follow set of \(expr\).

We now have enough information to write an algorithm to compute follow sets.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

compute_follow_set(non_terminal):

{

follow_set = {}

for production in productions {

production_body = production.get_body()

if the given non terminal does not appear in the production body:

continue

if the given non terminal is not the last symbol of the production_body:

follow_set.union_with(compute_first_set(symbol following the given non terminal))

else:

production_head = production.get_head()

follow_set.union_with(compute_follow_set(production_head))

return follow_set

}

Let us try the above algorithm on our arithmetic grammar which is repeated below.

Complete arithmetic grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term \\ expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{-} term \\ expr & \rightarrow term \\ term & \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow term \space \underline{/} \space f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow f\!actor \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{number} \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{(} expr \underline{)} \end{align*} $$Here is the execution of “compute_follow_set(factor)”.

We can now go back to making decisions at parsing steps. We can now answer both questions we posed earlier. The statements below cannot be justified in a formal way and hence we will call them heuristics. These heuristics will always work for the grammars we will consider and they work for grammars that common occur in programming language syntax specifications.

- The first question was about deciding whether to shift or to reduce at each parsing step. The answer is this. If we reduce the top stack contents and the resulting non terminal has the following token in its follow set, we reduce. Otherwise, we shift.

- If we can choose between multiple productions, we choose the one which reduces the maximum of the stack contents.

Let’s see an example of how these heuristics can be applied in practice. We will parse “(number - number) * number” using our arithmetic grammar. Before we do our parsing, we should write down the follow sets of each non terminal.

The initial state of the parser is this.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((number - number) * number\) |

There is nothing on the stack so we do a shift.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((\) | \(number - number) * number\) |

No non terminal has \(number\) in its follow set so we shift again.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((number\) | \(-\space number) * number\) |

\(-\) is in the follow set of \(f\!actor\) and the production \(f\!actor \rightarrow number\) matches the top symbol of the stack. Therefore, we use our first heuristic and give preference to reduce over shift by applying \(f\!actor \rightarrow number\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((f\!actor\) | \(-\space number) * number\) |

Since \(-\) is in the follow set of \(term\) and the production \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\) matches the top symbol of the stack, we apply \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((term\) | \(-\space number) * number\) |

\(-\) is also the follow set of \(expr\) and we can apply \(expr \rightarrow term\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr\) | \(-\space number) * number\) |

We cannot do any more reductions so we do a shift.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr \space -\) | \(number) * number\) |

We do a shift again since \(number\) is not in the follow set of any non terminal.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr \space - number\) | \() * number\) |

Now, \()\) is in the follow set of \(f\!actor\). Thus, we reduce the top symbol using \(f\!actor \rightarrow number\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr \space - f\!actor\) | \() * number\) |

\()\) is in the follow set of \(term\) as well so we apply \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\) to the top symbol of the stack.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr \space - term\) | \() * number\) |

We know that \()\) is in the follow set of \(expr\). But we have two choices of productions that we can apply: \(expr \rightarrow term\) and \(expr \rightarrow expr - term\). Following our second heuristic, we should match the maximum of the stack contents that we can and therefore apply \(expr \rightarrow expr -term\) on the top three symbols of the stack.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr\) | \() * number\) |

We cannot do any more reductions so we shift.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \((expr)\) | \(*\space number\) |

\(*\) is in the follow set of \(f\!actor\) and \(f\!actor \rightarrow (expr)\) matches all of the stack contents. We can do a reduction.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(f\!actor\) | \(* \space number\) |

\(*\) is in the follow set of \(term\). After applying \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\), we get the following.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(term\) | \(* \space number\) |

We cannot do any more reductions so we do a shift.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(term \space *\) | \(number\) |

We do a shift again since \(number\) is not in the follow set of any non terminal.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(term \space * number\) | \(\) |

We are stuck now. We cannot do any more moves but we still haven’t reduced the stack contents to the start symbol. We need to introduce more features into our parser to get past this stuck state.

We introduce the convention that every input is ended by “$”. The “$” symbol is not a part of the grammar and is introduced to mark the end of the inputs we will be parsing.

Suppose we start with the input “number + number $”. With our arithmetic grammar, it will be reduced to “expr $”. In general, every start symbol is going to have “$” is in its follow set. Thus, the follow sets of arithmetic grammar that we computed above need revision.

We now replay all the parsing steps we did above.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\) | \((number - number) * number\space $\) |

| \((\) | \(number - number) * number\space $\) |

| \((number\) | \(-\space number) * number\space $\) |

| \((f\!actor\) | \(-\space number) * number\space $\) |

| \((term\) | \(-\space number) * number\space $\) |

| \((expr\) | \(-\space number) * number\space $\) |

| \((expr\space -\) | \(number) * number\space $\) |

| \((expr - number\) | \() * number\space $\) |

| \((expr - f\!actor\) | \() * number\space $\) |

| \((expr - term\) | \() * number\space $\) |

| \((expr\) | \() * number\space $\) |

| \((expr)\) | \( *\space number\space $\) |

| \(f\!actor\) | \( *\space number\space $\) |

| \(term\) | \( *\space number\space $\) |

| \(term \space *\) | \(number\space $\) |

| \(term * number\) | \(\space $\) |

We have \($\) in the follow set of \(f\!actor\). We thus apply \(f\!actor \rightarrow number\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(term * f\!actor\) | \(\space $\) |

We have \($\) in the follow set of \(term\) and we can match all of the stack contents using \(term \rightarrow term * f\!actor\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(term\) | \(\space $\) |

Finally, \($\) is in the follow set of \(expr\). We can apply \(expr \rightarrow term\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(expr\) | \(\space $\) |

Since we have reduced the input to the start symbol, our parsing has finished succesfully.

We now have a definite framework to execute parsing actions and make parsing decisions. But we need to make the above mechanisms and policies more amenable to implementation. In the next section, we will recast the above framework as a graph problem.

Implementing parsers using automata

In the last section, we arrived at a framework for making parsing decisions. We now have all the ingredients we need to construct a parser programmatically given a context-free grammar. In this section, we will implement context-free grammars using a specific type of automaton.

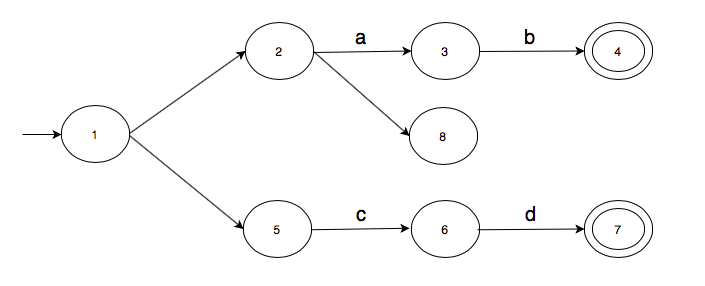

Let us start by doing a quick review of the basics of finite automata. A finite automaton is a labelled directed graph where the vertices of the graph are called the states and the edges are called the transitions. Each finite automaton has:

- A set of states.

- A state identified as a start state.

- A set of states identified as final states.

- An alphabet which is the set of symbols that can label transitions.

- A transition function which takes a state and an alphabet symbol as inputs and outputs a set of states.

Here is an example.

The automaton makes moves on a given string. For example, for string “ab”, the above automaton makes the following moves.

How can we use finite automata to track parser state? To examine that, let us go back to the simplest grammar we had at the beginning.

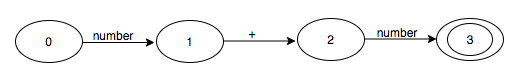

Addition with two operands grammar

Start symbol: expr

$$ \begin{align*} expr & \rightarrow \underline{number} \underline{+} \underline{number} \\ \end{align*} $$We can construct a finite automaton that recognises the body of the production.

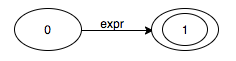

We can also construct a finite automaton to recognise the head of the production.

When we are scanning some input from left to right, we can use the body automaton to keep track of where we are in the input. After we have reduced the input to the production head, we can use our head automaton to see if the reduced string is correct.

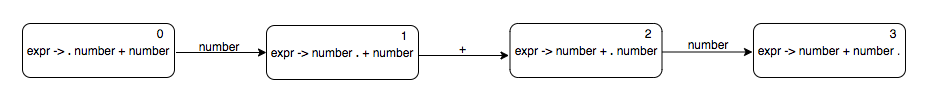

We can track where we are in a production with a dot in the production body. Here are some examples.

It is formally defined like this.

Definition 7: Production item

A production item is a production with a dot before a symbol in the body.

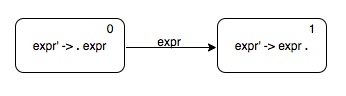

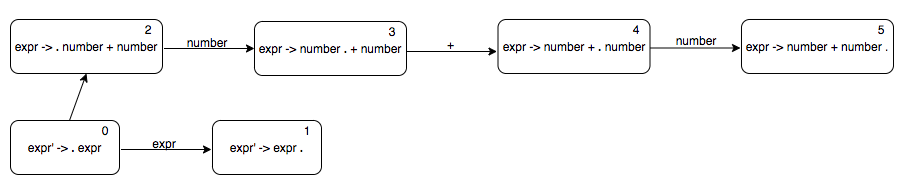

We can now redraw our body automaton using production items.

If a string takes the above automaton to state 3, we should reduce using the production \(expr \rightarrow \underline{number} \underline{+} \underline{number}\). How can we check whether we have correctly reduced to the head of the production? We can construct a new automaton for the head. To make that more convenient, we augment our grammar with a new production and a new start symbol.

Augmented addition with two operands grammar

Start symbol: expr'

$$ \begin{align*} expr' & \rightarrow expr \\ expr & \rightarrow \underline{number} \underline{+} \underline{number} \\ \end{align*} $$We can now make an automaton to recoginse the string “expr”. Let us call it the head automaton.

The sequence of things that need to happen for our addition grammar to accept a string is this.

- The string takes the body automaton to state 3.

- Once we reach the state 3, we reduce using the addition grammar production.

- We now have the head of the production as the input string. We confirm that by executing the head automaton using the reduced string and checking whether it goes to state 1.

There are gaps between these steps that we need to fill. How can we construct a single automaton to execute the above steps. We somehow have to do this.

- We traverse the body automaton using the input string.

- Once the body automaton scans the input string corresponding the body of a production, we do a reduction.

- We traverse the head automaton using the reduced string.

The way to achieve this is by pushing the current state of the automaton on a stack after each transition. Earlier, we implicitely tracked our current state using a single variable. If we push the current state after each transition to a stack, it would enable us to “revert” the steps the automaton took.

Let us now see how can we construct an automaton for a grammar. We start with the start symbol production.

When we are at state 0, we can either see \(expr\) or something that is derived from \(expr\). So we need to have two transitions out of state 0, one with the label \(expr\) and one with an \(\epsilon\)-transition to a "sub-automaton" to recognise the body of \(expr\), which is \(number + number\).

Let us try to parse “number + number” using the above automaton and a stack. We represent the stack contents by writing down the elements of the stack seperated by commas such that the top of the stack is on the right. Initially, the stack consists of the start state of the automaton.

After reading “number”, the automaton goes to state 3. We push that state on to the stack.

After reading “+”, we push state 4 onto the stack.

Finally, we ready “number” and the new stack state looks like this.

We now do a reduce using the production \(expr \rightarrow \underline{number} \underline{+} \underline{number}\). When we do a reduce, we pop as many elements from the stack as there are symbols in the body. That leads us back to the state we were in when we started parsing the production body. Since the length of the body of this production is three, we pop three elements from the stack. The current stack looks like this.

We have reduced the string to “expr”. We now restart the automaton with “expr” as the input. The stack looks like this after reading “expr”.

The current state of the automaton corresponds to the input reduced to the start symbol. Hence, the automaton has parsed “number + number” succesfully.

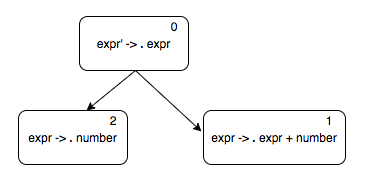

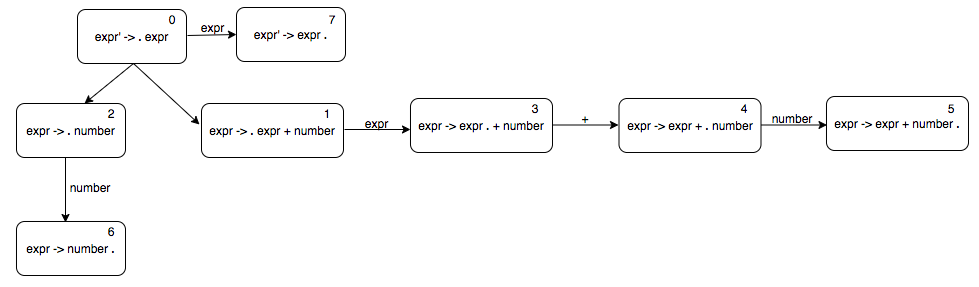

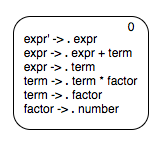

Let us try a slightly more complex grammar. We augment our original complete addition grammar with a new start symbol.

Augmented addition grammar

Start symbol: expr'

$$ \begin{align*} expr' & \rightarrow expr \\ expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number} \\ expr & \rightarrow \underline{number} \end{align*} $$As above, we start with the start symbol production state.

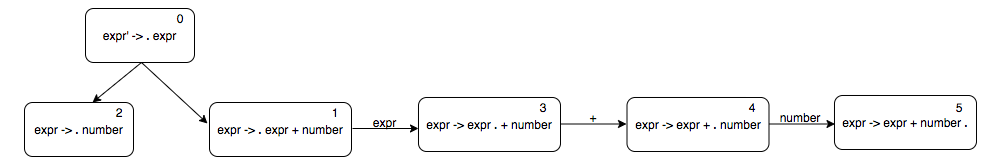

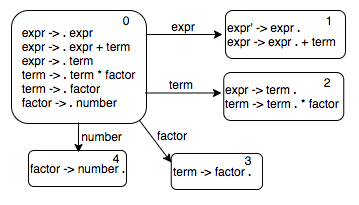

Let us focus first on computing the \(\epsilon\)-closure of this state. An \(\epsilon\)-closure of a state is that state itself along with all the other states reachable from that state following \(\epsilon\) moves alone. In our context, it means that if the dot is before a non terminal, we can either see that non terminal or some string derivable from that non terminal. So we add as many \(\epsilon\) transitions as there are productions of the non-terminal that appears next to the dot.

From state 1, we do not need to compute \(\epsilon\)-closure for the productions of \(expr\) since we have already included all \(expr\) productions in states 0, 1, and 2.

Starting from state 1, we can include all the states to process “expr + number”.

We can similarly add the states to process “number” from state 2, and to process “expr” from state 0.

Let’s parse “number + number + number” using our above automaton. We will write the stack states on the left and the input that remains to be parsed on the right. The start state looks like this.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}\) | \(number + number + number\) |

After reading the first token, we reach state 6. The parser state now looks like this.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{6\}\) | \(+\space number + number\) |

State 6 indicates that we should reduce using \(expr \rightarrow number\). We now need to "revise our history" and transition to the state we would have reached after reading "expr" from \(\{0, 1, 2\}\) instead of "number". We do two things.

- We pop as many elements from the stack as there are symbols in the body. In our case, we pop off one state.

- Now we know the state we originally had and we know the string we want to process, which is the head \(expr\). We therefore push the state reachable from 0 using \(expr\). The parser state looks like this now.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}\) | \(+\space number + number\) |

State 7 suggests that we should do a reduce using \(expr' \rightarrow expr\). But we shouldn't because + is not in the follow set of \(expr'\). To make further progress, we should compute the follow sets of \(expr'\) and \(expr\). We should also re-introduce the convention of terminating the inputs by the symbol "$". The follow sets look like these.

Let us continue processing our string using the automaton. There is nothing we can do from state 7 but from state 3, we can follow a transition to state 4 using “+”.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}\) | \(number + number \space $\) |

From 4, we can go to 5 following “number” transition.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}, \{5\}\) | \(+ \space number \space $\) |

State 5 indicates that we should reduce using \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number}\). And we can do that because \(+\) is in the follow set of \(expr\). Thus, we pop off three elements from the stack and follow the "expr" transition out of state \(\{0, 1, 2\}\).

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}\) | \(+ \space number \space $\) |

Like above, we can read “+” and “number” in succession. The state after reading the next two tokens is this.

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}, \{5\}\) | \($\) |

We are in state 5 and $ is in the follow set of \(expr\). We can thus reduce using \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{+} \underline{number}\) by popping off three symbols and following \(expr\) out of \(\{0, 1, 2\}\)

| Stack | Input |

|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}\) | \($\) |

Finally, we cannot do anything from state 7 but $ is in the follow set of \(expr'\) and so we can reduce using \(expr' \rightarrow expr\). Since we have reduced the input string to \(expr'\), we say that we have parsed the input successfully.

Let’s compare the automaton framework that we just discussed with the stack framework that we discussed before. We can do a side-by-side comparison of parsing “number + number + number” using addition grammar.

| Automaton stack | Framework stack | Input |

|---|---|---|

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}\) | \(number + number + number\space $\) | |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{6\}\) | \(number\) | \(+ \space number + number\space $\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}\) | \(expr\) | \(+ \space number + number\space $\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}\) | \(expr\space +\) | \(number + number\space $\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}, \{5\}\) | \(expr\space + number\) | \(+ \space number\space $\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}\) | \(expr\) | \(+ \space number\space $\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}\) | \(expr \space +\) | \(number\space $\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}, \{4\}, \{5\}\) | \(expr \space + number\) | \($\) |

| \(\{0, 1, 2\}, \{3, 7\}\) | \(expr\) | \($\) |

The symbols on the framework stack are exactly those that drive the automaton. Hence, the automaton framework is equivalent to the stack framework. And because the automaton is a directed graph, we can use the standard graph data structures and algorithms to implement it.

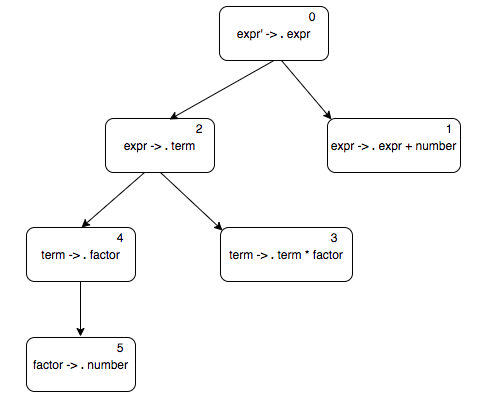

Let us try a slightly more complicated example. Here is the augmented addition and multiplication grammar.

Augmented addition and multiplication

Start symbol: expr'

$$ \begin{align*} expr' & \rightarrow expr \\ expr & \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term \\ expr & \rightarrow term \\ term & \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor \\ term & \rightarrow f\!actor \\ f\!actor & \rightarrow \underline{number} \\ \end{align*} $$Here is the start state and its closure set. Remember that if there is a dot before a non terminal, we need to add \(\epsilon\)-transitions to all the productions of that non terminal. So we add \(\epsilon\)-transitions out of state 0 to the \(expr\) productions, from state 2 to \(term\) productions, and from state 4 to \(f\!actor\) productions.

In general, we can compute the \(\epsilon\)-closure of an item by doing a breadth first search on \(\epsilon\)-transitions. The algorithm looks like this

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

compute_epsilon_closure(item, grammar):

epsilon_closure_set = {item}

queue.enqueue(item)

while queue is non-empty {

current_item = queue.dequeue()

if current_item has dot before a non terminal:

for production in productions of non terminal:

next_item = construct item for the production with dot on the left side of the body

if next item is not already in the epsilon closure set

epsilon_closure_set.add(next_item)

queue.enqueue(next_item)

To make the illustrations concise, we collect all the items that belong to the same closure set into item sets. The above closure set looks like this.

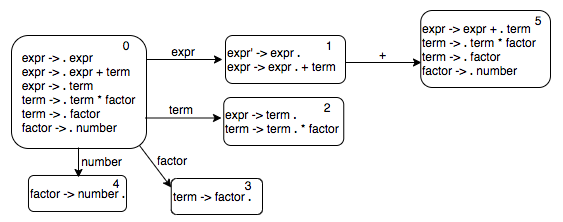

To figure out the states reachable from state 0, we check the symbols next to the dot for each item and make those transitions out. So for state 0, there will be four transitions, one each with label \(expr\), \(term\), \(f\!actor\), and \(number\). The states reachable from 0 look like this.

We can continue in breadth-first search fashion. Let us now look at the state 1. There is only one transition out of that state, the one with the label +. We compute the epsilon closure of the new state; it looks like this.

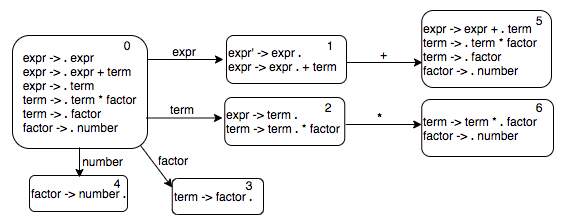

Continuing with our breadth first search, we next look at state 2. There is one transition out of that state with label *.

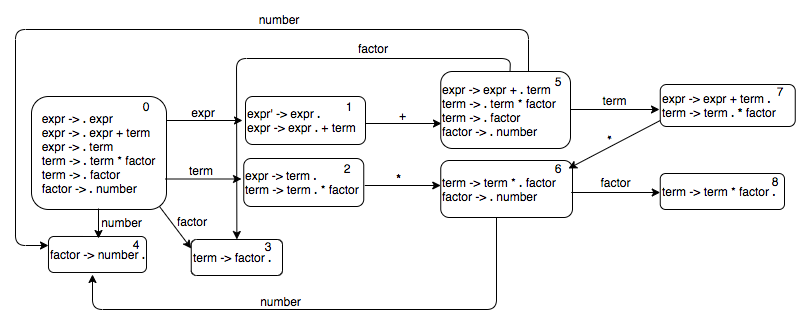

We can keep expanding the transition graph using the breadth first search. The complete automaton looks like this.

The above graph can be represented by the following adjacency list.

{

0: {"expr": 1, "term": 2, "factor": 3, "number": 4},

1: {"+": 5},

2: {"*": 6},

5: {"term": 7, "factor": 3, "number": 4},

6: {"factor": 8, "number": 4},

7: {"*": 6}

}

However, there are some differences between directed graphs and the above automaton.

- When we reach a new state, we push that state on to the stack. That is, we do a shift.

- When we reach a state where any of the items has the dot on the right side of the body, we do a reduce using that production, depending on the next input token.

We need to modify our above representation to handle shift and reduce actions. To support shift, we add a prefix “s” to each state that is the result of a state and a transition symbol.

{

0: {"expr": "s1", "term": "s2", "factor": "s3", "number": "s4"},

1: {"+": "s5"},

2: {"*": "s6"},

5: {"term": "s7", "factor": "s3", "number": "s4"},

6: {"factor": "s8", "number": "s4"},

7: {"*": "s6"}

}

To add support for reduce, we first number all the productions so that we can refer to them.

Next, we compute the follow set of each non terminal.

Let's take state 7 of the above automaton as an example. It has an item of production 2 with the dot on the right side of the production. We do a reduce using production 2 if we are in state 7 and the next input token is either \(+\) or \($\) which are in the follow set of \(expr\). We add that information to our data structure by adding the entry "r2" for \((7, +)\) and \((7, $)\) in the automaton.

{

0: {"expr": "s1", "term": "s2", "factor": "s3", "number": "s4"},

1: {"+": "s5"},

2: {"*": "s6"},

5: {"term": "s7", "factor": "s3", "number": "s4"},

6: {"factor": "s8", "number": "s4"},

7: {"*": "s6","+", "r2", "$", "r2"}

}

In general, to fill in the reduce moves in our above data structure, we need to do these things:

- We look at each state and select those that have at least one item with the dot on the right side.

- For each symbol in the follow set of the head of the reducible item, we add entries for that state and that symbol for the correponding reduction.

The above data structure called a parsing table. It can be constructed by doing a breadth first search.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

construct_parsing_table(grammar):

productions_list = grammar.get_productions()

start_production = grammar.get_start_production()

start_item_set = construct_item_set(start_production)

queue.enqueue(start_production)

parsing_table = {}

# BFS to compute shift moves.

while !queue.empty():

current_state = queue.dequeue()

for transition_symbol in current_state.get_transition_symbols():

next_state = current_state.compute_next_state(transition_symbol)

parsing_table.add_entry(current_state, transition_symbol, next_state)

# Compute reduce moves by scanning all the states.

for item_set in all_item_sets():

for item in item_set.get_reducible_items():

if item has dot on the right hand side:

production = item.get_production()

production_head = production.get_head()

production_number = production.get_number()

for symbol in follow_set(production_head)

state = item_set.get_state()

parsing_table.add_entry(state, symbol, "r production_number")

return parsing_table;

}

Using the above algorithm, the parsing table of the addition and multiplication grammar looks like this.

{

0: {"expr": "s1", "term": "s2", "factor": "s3", "number": "s4"},

1: {"+": "s5", "$": "r1"},

2: {"*": "s6", "+": "r3", "$": "r3"},

3: {"+": "r5", "*": "r5", "$": "r5"},

4: {"+": "r6", "*": "r6", "$": "r6"},

5: {"term": "s7", "factor": "s3", "number": "s4"},

6: {"factor": "s8", "number": "s4"},

7: {"*": "s6", "+", "r2", "$", "r2"},

8: {"+": "r4" "*": "r4", "$": "r4"}

}

Let us do an example run of the above parsing table on the input “number + number * number”. We add a column for explanations.

| Parser stack | Input | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| \(0\) | \(number + number * number \space $\) | Shift \(4\). |

| \(0, 4\) | \(+ \space number * number \space $\) | Reduce using production 6, \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\), and transition from \(0\) on \(f\!actor\). |

| \(0, 3\) | \(+ \space number * number \space $\) | Reduce using production 5, \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\), and transition from \(0\) on \(term\). |

| \(0, 2\) | \(+ \space number * number \space $\) | Reduce using production 3, \(expr \rightarrow term\), and transition from \(0\) on \(expr\). |

| \(0, 1\) | \(+ \space number * number \space $\) | Shift \(5\). |

| \(0, 1, 5\) | \(number * number \space $\) | Shift \(4\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 4\) | \(*\space number \space $\) | Reduce using production 6, \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\), and transition from state \(5\) on \(f\!actor\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 3\) | \(*\space number \space $\) | Reduce using production 5, \(term \rightarrow f\!actor\), and transition from state \(5\) on \(term\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 7\) | \(*\space number \space $\) | Shift \(6\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 7, 6\) | \(number \space $\) | Shift \(4\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 7, 6, 4\) | \($\) | Reduce using production 6, \(f\!actor \rightarrow \underline{number}\), and transition from state \(6\) on \(f\!actor\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 7, 6, 8\) | \($\) | Reduce using production 4, \(term \rightarrow term \underline{*} f\!actor\), and transition from state \(5\) on \(term\). |

| \(0, 1, 5, 7\) | \($\) | Reduce using production 2, \(expr \rightarrow expr \underline{+} term\), and transition from state \(0\) on \(expr\). |

| \(0, 1\) | \($\) | Reduce using production 1, \(expr' \rightarrow expr\), and accept. |

Notice that all the information we need to make parsing moves is contained in the parsing table. We no longer need to look at a production list or follow sets to execute parsing actions. We thus have solved the main problem we were pursuing. Parsing tables are the implementations for context-free grammars.

Conclusion

What is the output of a parser? We can return a boolean indicating whether the input is parseable. But we need to return more information. Specifically, the reduce moves we did might be interesting to the later phases of the compiler.

We need to define more concepts before we can discuss the output of a parser. Specifically, we need to execute actions whenever a reduction happens. This subject will be treated in the next article.